|

Puppet Wranglers In the theatre, Rhinoceros and War Horse question human relations with the natural world. Eleanor Margolies reports on the power of puppetry to enact animal and human behaviour.

Handspring Theatre Company:

War Horse |

Someone has let the animals loose on stage. At the Royal Court, Eugène Ionesco’s play Rhinoceros demands a herd of rampaging rhinoceroses, while War Horse, Nick Stafford's adaptation for the National Theatre of Michael Morpurgo’s novel, has a horse at its emotional centre.

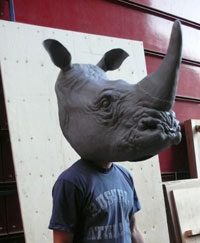

Both of these productions involve research into animal behaviour, but with quite different emphases. In Rhinoceros, realistic masks and a life-size puppet are combined with an expressionist transformation of the actor’s body and movement. In War Horse the animal observation determines the design and movement of the life-like but non-realistic animal puppets who 'act' alongside the humans. Both productions question our understanding of the natural world and the boundaries between animal and human behaviour.

Dudard: What’s more natural than a rhinoceros?

Bérenger: Yes – but a man turning into a rhinoceros – that’s unquestionably abnormal.

Ionesco, Rhinoceros

The Rhinoceros company watched videos, contacted the campaigning organisation SOS Rhino, and took a field trip to Colchester Zoo. Actor Zawe Ashton saw an image from the play reflected in the rhino’s physiognomy: ‘a huge, glazed eye, lost in the armour of the body’, as if a human being were trapped inside. But for Jasper Britton, the rhinoceroses were ‘a bit too sweet… too cuddly’.

The actors’ observations – and their empathy for the animal Other – had to be converted into a theatrical movement vocabulary. Working with director Dominic Cooke and movement director Sue Lefton, the actors explored ways of changing the alignment of the spine and their gaze.

As 'Jean', Britton transforms himself in the course of a single scene from a man with a sore head to a furious animal. He directs his face straight downwards to the floor, his bare shoulders round inwards so that his chest becomes barrel-like, and his legs propel him powerfully towards a wall. Stopping just before he crashes into it, he trots on the spot, as if puzzled by this inexplicable barrier. He seems to be trying out a new physicality as he

argues for a new philosophy of Nature:

Rhinoceros puppet head |

Jean: ‘Don’t give me moral values – I’m sick of moral values ... We need to rediscover our primordial wholeness’.

'Jean’s' transformation is aided by make-up and a series of masks, until at last he crashes through a wall as a full-size rhinoceros. The combination of physical acting with realistic masks and puppets makes his transformation from human to rhinoceros believable. At the same time, it seems to be the result of an act of will. As is said of another character:

‘Maybe [he] felt he needed to let go after all those years behind a desk’. Ionesco’s exploration of this desire to ‘be natural’, to put aside moral scruples and join the herd, takes the play beyond surreal fantasy to imply a political dimension.

‘You should never talk to horses, Albert … They never understand you. They’re stupid creatures. Obstinate and stupid, that’s what your father says, and he’s known horses all his life.’

Michael Morpurgo, War Horse

The war horse, Joey |

In contrast to Rhinoceros, War Horse draws attention to the otherness of the horse rather than to the possibility of humans becoming animal. War Horse is a collaboration between the National Theatre and the South African puppet company Handspring, founded by Adrian Kohler and Basil Jones.

The movement of Handspring's puppets – from the gawky stiff-legged colt to the fully-grown horses which stretch their necks, rear up on two legs and even carry human riders – is breathtakingly real. They ‘breathe’ and quiver when stroked. Moreover, they seem to employ all the non-verbal means of communication used by real horses: shifts of weight, neighs, whickering and snorts, a turn of the ear or a flicking tail. This rich expressive detail is essential because while the horse Joey himself narrates Michael Morpurgo’s novel, in the stage adaptation, his viewpoint must be suggested without words. Joey sees the First World War from both sides: he is sold to the British cavalry, pulls a hospital cart and a gun for the German army, works on a French farm and, after being caught on barbed wire in no-man’s land, is reunited with Albert, the Devon farmer’s son who has followed him into the army.

Joey and Topthorn |

The horse puppets designed by Kohler are of cane, bent into curving shapes that suggest the underlying anatomy, and lined with a translucent skin that highlights the sculptural form. Two puppeteers are visible inside the horse (which is slightly larger than life-size), and a third stands outside to manipulate the head. Their visibility does not detract from the imagined life of the horse. This is partly because we are used to seeing humans alongside horses, but it is also because unconcealed animation is part of the aesthetic of the whole piece. The audience can see how images are constructed, whether it is

farmers holding poles horizontally to represent a fence or a shadow puppeteer adding painfully live, jerky soldiers to a projected image of exploding shells. While the illusion that the horses are moving independently is bewitching, the presence of puppeteers is a reminder that these horses are not animals observed in nature but animals enlisted in human life: in agriculture, warfare and theatre.

The physical characterisation of the horses is based on extensive research and observation, from watching videos of the work of Monty Roberts (the ‘horse whisperer’) to a

visit to a Kent farm run by the Working Horse Trust. Such research, says Basil Jones, ‘is about deepening the company’s empathy and understanding’ of animals. It ‘feeds into the performance in subtle ways’, informing the devising of non-verbal scenes such as the aggressive first encounter between two stallions, Joey and Topthorn.

Members of the company – directors, actors, writer and designer – also met soldiers of a mounted artillery regiment, the King’s Troop, as they groomed their horses and carried out military manoeuvres on Wormwood Scrubs. One soldier, says Jones, told ‘the story of the death of a horse during a public parade and how the other horses were affected by it – not eating for several days’. This story gave substance to a scene in which Joey realises that

Topthorn has died: ‘Our knowledge of how real horses were affected by the death of their friends – and that horses do have friends – is very important in the way we approach and develop this scene.’

The two-year-long development of War Horse allowed puppetry to be developed as a theatrical language throughout the piece, rather than as a one-off special

effect. The audience has time to pass from initial wonder through curiosity about technicalities to an understanding of the design and movement vocabulary.

Kohler and Jones' animals are neither cuddly, anthropomorphised creatures, nor naturalistic portraits. In their other recent productions, as with War Horse, the constructed nature of the puppet is always displayed in order to explore the role animals play in human life.

The Chimp Project |

Seven years ago, for The Chimp Project, Handspring travelled to the Gombe Stream National Park in Tanzania, where Jane Goodall has been observing chimps for 40 years, read the academic Donna Haraway’s exploration of ‘the unacknowledged agendas’ behind chimpanzee research and met American researchers who had taught captive chimps to use sign language in the 1960s and 70s. Kohler and Jones designed puppets which could move with extraordinary realism, but made sure that the audience would always be aware that they were puppets. Despite the importance of grooming in the chimps’ social life, the puppets were not covered with fur. Instead, the underlying structure of the bodies - interlocking plywood planes covered with a semi-transparent skin – was left visible. The aim was not the carefully-crafted ‘naturalness’ of filmed documentaries, but rather, said Kohler, ‘to problematise the very idea of Nature and the Natural’.

Ubu and the Truth Commission, included a vicious crocodile with a body made of an old canvas kit-bag. The crocodile was fed documents and videos to ‘shred’ and ‘swallow’, drawing attention to the fragility of physical evidence, and the malicious or self-serving motives of those who destroy it. As William Kentridge, the director of the production, wrote later, there was in South Africa at this period ‘a battle between the paper shredders and the photostat machines’. While a ‘real machine, noisily and slowly going through reams of paper, did not seem very remarkable’, the surreal crocodile-shredder (and a terrifying puppet police-dog) evoked the violence of the apartheid state. The production also used puppets to represent real people who had testified to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, avoiding the natural tendency of spectators to focus on the ‘performance’ or ‘conviction’ of an actor, and instead emphasising the significance of the spoken words.

Ubu and the Truth Commission |

The power of puppetry to represent things that are ‘impossible’ to stage – vast landscapes, imaginary worlds, a herd of rhinoceroses or the horrific experiences of war – comes from an audience’s ability to see with ‘double-vision’, perceiving both the material reality of the puppet and the fiction it represents. Since the observation of animals also involves a kind of ‘double vision’, in which the human viewpoint is always present even as we try to understand that of the animal, there remains much more to explore in the potential of puppets to dramatise both the natural world and human relationships to it.

© Eleanor Margolies

Eleanor Margolies edits Puppet Notebook, the magazine of British UNIMA, Union Internationale de la Marionette. UNIMA's website is www.unima.org.uk See also Kellie Gutman's feature here, War Horse: working with animals at the National Theatre.

Photo credits:

Photographs of War Horse by Simon Annand © the National Theatre

Photographs of Handspring's The Chimp Project and Ubu and the Truth Commission by Ruphon Coudyzer © Handspring

Photographs of research and rehearsal of Rhinoceros by Paul Handley © the Royal Court Theatre

Rhinoceros is at the Royal Court until 15 December.

War Horse is on at the National Theatre until 14 February 2008.

published in 2007

|

The power of puppetry to represent things that are ‘impossible’ to stage – vast landscapes, imaginary worlds, a herd of rhinoceroses or the horrific experiences of war – comes from an audience’s ability to see with ‘double-vision’, perceiving both the material reality of the puppet and the fiction it represents. While the illusion that the horses are moving independently is bewitching, the presence of puppeteers is a reminder that these horses are not animals observed in nature but animals enlisted in human life: in agriculture, warfare and theatre.

|